The Idea for Sixpence for a Slaughter - Matthew's Latest Murder Investigation

Share

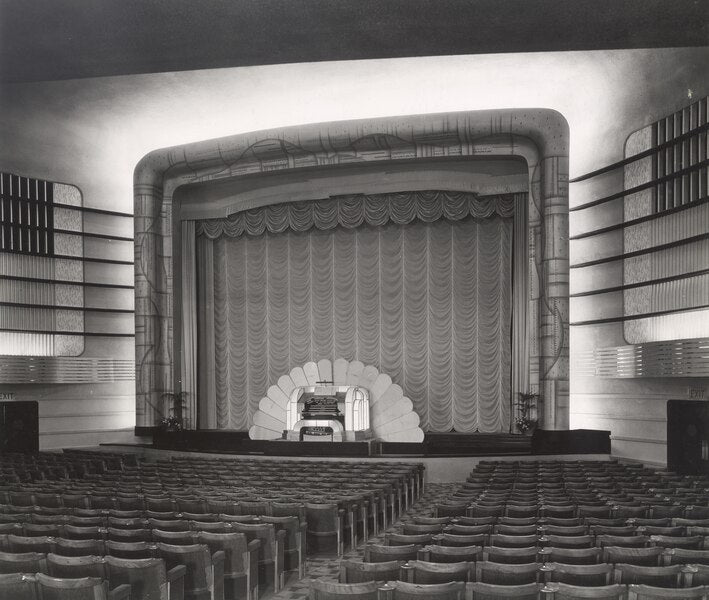

The idea for the story of my latest novel, Sixpence for a Slaughter, came from the conflation of two incidents. The first occurred when I was in a cinema a few years ago and was distracted about twenty minutes into the film by a man entering the auditorium and standing at the bottom of the stairs and just staring up over the auditorium. It struck me as odd, though he was probably a staff member checking the number of people in there or something else perfectly innocuous. However, my writer's brain kicked into gear and started me thinking how I and my fellow cinemagoers were literally a captive audience, and that if he had decided to do something criminal, we would have been at his mercy. Yes, I can be a little bit paranoid.

The second incident was my reading of a newspaper article from 1929 about the Glen Cinema tragedy when toxic gas filled the auditorium, causing a panic among the children attending the matinee and resulting in 71 deaths and many others injured. Yes, a very grisly true story, but it was fodder for the pivotal scene in Sixpence. But where my cinema tragedy was a deliberate murder, the Glen Cinema incident was a terrible accident. What exactly happened?

On December 31, 1929, the Glen Cinema in Paisley, just outside of Glasgow, was filled predominantly with children, eager to watch a Western during the holiday matinee. Unbeknownst to the excited audience, a catastrophic sequence of events was about to occur. The root cause was a canister of highly flammable nitrate film which had just been shown and was improperly stored in a metal container. The film overheated and began to emit thick, toxic smoke filled with poisonous gases.

As smoke filled the air, panic ensued. The young audience rushed to the exits, but their escape was impeded by the cinema’s inward-opening doors. It is also believed that the exits were padlocked. In the crush that followed, 71 children tragically lost their lives, not from the smoke or fire directly, but from the suffocating press of the crowd trying to escape.

The media response to the disaster was swift and extensive. Newspapers across Britain and beyond covered the tragedy in detail, focusing on the harrowing accounts of survivors and the bereaved. Blame was laid at the cinema for locking exits and not providing enough of them. The owner admitted these shortcomings but claimed he had instructed that no exits were to be locked during film showings. As a result, the manager, James Dorward, was put on trial for culpable homicide but found not guilty.

Press coverage played a critical role in catalysing changes in public safety standards. The tragedy was portrayed not only as a heart-breaking incident but also as a dire warning of the dangers of flammable film materials and inadequate safety measures in public entertainment venues.

Editorials and opinion pieces of the time expressed outrage over the conditions that had allowed such a disaster to occur, particularly criticising the lack of proper emergency exits and the use of highly flammable film stock. The graphic descriptions of the chaos and the poignant stories of young lives lost painted a grim picture that spurred public demand for change.

In response to the public outcry and the press coverage, there was a marked shift in regulatory measures for cinemas. One of the most significant changes was the mandate that all exit doors in cinemas must open outwards to prevent similar tragedies. This regulation became a standard safety requirement, a direct consequence of the Glen Cinema disaster.

Furthermore, the incident led to a broader discussion about the safety of nitrate film, which was known for its volatility but continued to be used because of its superior aesthetic qualities. The Glen Cinema tragedy highlighted the urgent need for safer alternatives, which would eventually lead to the industry-wide adoption of "safety film" in the decades following.

Read Sixpence for a Slaughter.

Image credits:

John Maltby, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons